At the end of each year, I’ve usually written a “most popular articles of the year” type of article. Last year, however, I wrote a slightly longer “year in review” type of post. Given that we’re at the end of another year and I enjoyed writing about 2024, I thought it worth the time to do another one for 2025.

For the most part, I’m sticking with the same format as last year covering what I’ve read, listened to, and how I did with some of my other goals. I’m also adding a couple of sections related both to work and other projects that I completed (or at least started) this year.

Highlights of 2025

Work

I don’t talk much about my day-to-day here and haven’t so far as posted anything other than a link to a blog post on X or any other social media for at least a year.

I enjoy my work on the R&D team at Awesome Motive where the last year has been spent deep in AI, working in Laravel, Google Cloud Platform, WordPress, and other tangential tools.

Much of the work we’re doing is building out tools and infrastructure that supports security initiatives, software for internal teams, and other utilities that are best described to fall under DevOps.

Projects

This year is the first time in a few years where I not only worked on a number of different side projects, but I worked on projects that use tech stacks with which I don’t frequently work. The advent of AI has made is much easier to go from nothing to something faster all the while learning something new at a faster rate.

Here’s a short list of what I published this year in chronological order:

- Code Standard Selector for Visual Studio Code is a Visual Studio Code extension that makes it easy to switch your PHP coding standard without having to edit any settings in your IDE. And, yes, this will also work in any of the IDEs that are a fork of VS Code.

- Remove Empty Shortcodes is a WordPress plugin I’ve revisited that automatically removes empty or inactive shortcodes from your WordPress content while preserving your original database entries.

- TuneLink.io For Matching Music Across Services allows you to easily find the same song across different music streaming services. Simply paste a link from Spotify or Apple Music, and TuneLink will give you the matching track on the other platform.

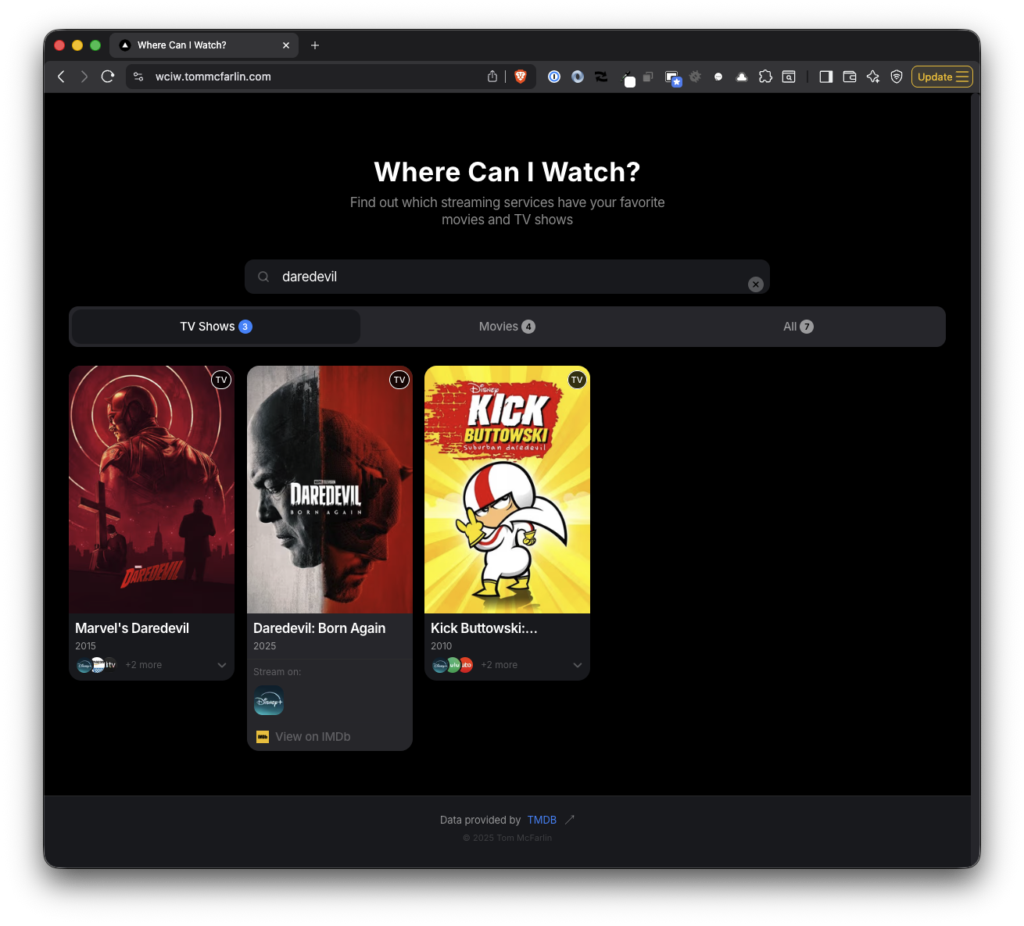

- Where Can I Watch? is a web application that helps users quickly find which streaming services offer a particular show or movie.

- Fetch Album Artwork for Apple Music Playlists is Python script to fetch album artwork for Apple Music playlists when given an artist and an album. This makes it a little bit easier to make sure album playlists have better looking artwork than what Apple Music generates on its own.

- TM Monthly Backup is an aptly titled program I use for easily backing up photos, videos, screenshots, and even generated content from my Apple Photos library.

Out of the various projects listed above, the ones about which I’ve received the most email are my monthly backup program, Where Can I Watch?, and Code Standard Selector.

Most Popular Posts

Last year, I shared the most popular posts that I’d published in 2024. This year, I thought it interesting to look at the most popular posts in terms of visits over the year as well as the most popular posts of 2025.

Popular Posts By Traffic in 2025

- Installing Old Versions of PHP With Homebrew

- Writing Messages to the WordPress Debug Log

- A Quick Guide to Shells in macOS

- How To Configure Laravel Herd, Xdebug, and Visual Studio Code

Popular Posts Published in 2025

As years have passed, there’s an obvious shift in content an frequency but it’s neat to see the long tail some of these posts have (namely those that are still popular in 2025).

Books

I still try to read two books at a time – one fiction and one non-fiction – but I don’t but hard limits on how many books per month or whether or not they are the latest best sellers or most popular books. I aim to read what I want to read.

At the time of this writing, I read 22 books this year. I won’t list them all but some of the ones I enjoyed the most are:

- Non-fiction

- Farenheit-182 by Mark Hoppus. Since I grew up listening to blink-182, this was a fantastic [and an easy] read. It hits a lot of high notes, glosses over some of the stuff that, although would’ve been interesting, wasn’t necessarily relevant to the core band.

- The Comfort Crisis by Michael Easter. I decided to read this after hearing Michael on a podcast. The overarching lesson of the book is still worth reading, and I won’t spoil anything here, but I really like Easter’s writing style. He intersperses his personal story with the larger points he’s making.

- On Writing by Stephen King. I’ve been reading his books for years so reading the only memoir he’s published and gaining insight into his process, along with some other fun anecdotes, made for a good read.

- Future Boy by Michael J. Fox. Back to the Future is one of my top five favorite movies (in fact, I think it’s one of the only good time travel movies that exist) and Michael J. Fox is an incredible person so reading this was an easy choice. If you haven’t seen the documentary Still, it plays well in conjunction with the content of this book.

- Fiction

- The Dark Tower VII by Stephen King. I was in the fourth book at the end of last year and wrapped the series up in February of 2025. It made for a really great adventure. Yes, it has its weak points but overall it’s hard to find a modern epic that’s as sprawling as this series.

- Sunrise on the Reaping by Suzanne Collins. I’ve enjoyed The Hunger Games since it was published and have also liked all of the additional stories Collins has written since. Given a choice between The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes, which I also liked, I like this one even more.

Obviously, it wasn’t a big year for fiction. If there’s an honorable mention at least for the sake of discussion it would be The Cabin at the End of the World by Paul Tremblay. It was a book I picked up on a whim unaware that the movie Knock at the Cabin was based on it. It had a terrific hook from the first page but the ending did not hold up to the quality of the rest of the story.

Fitness

In September of last year, I pinched a nerve in my lower back which brought my usual routine to a halt. I was able to get back to walking by November and was back running on a treadmill and pushing weights by January.

Since then, I’ve had to make adjustments to my usual workouts. I don’t run outside anymore, unfortunately, but I still exercise five times a week and have primarily been doing a combination of running on the treadmill, strength training, and stretching every day. Once you pinch a nerve in your back, you’ll do just about anything to prevent it from happening again.

I’m still using Gentler Streak and have all the usual stats to share but the one that’s most important to me, given where I was last year, is this: Since logging all of my exercise via my Apple Watch since 2016, this is the first year since 2018 that I’ve exercised more cumulative time in an entire year. At the time of this writing, I’ve logged 162 hours and 5 minutes and 437.69 miles in 2025.

I don’t have a goal of trying to surpass this next year but if I can maintain this (I’m not getting any younger) and if I can avoid any further issues with my back, then I’ll be happy.

Music, TV, and Podcasts

Music

The albums I enjoyed the most in 2025 include:

- Son of Dad by Stephen Wilson Jr

- Worthy by Anderson East

- Subtitles for Feelings by Patrick Droney

There’s a handful of other albums that I saved in Spotify this year (and, really, Subtitles for Feelings didn’t come out this year but I kept coming back to it). And for what it’s worth, there’s been a handful of synthwave and retrowave albums I listen to a lot when I work (most of them are by Timecop1983, FM-84, and The Midnight).

TV

As with last year, the majority of what I watch is whenever I’m on the treadmill or whenever Meghan and I are up for watching something before the day’s over. The shows I enjoyed most this year are (in no particular order):

- Daredevil: Born Again. Though it felt a bit different from the Netflix series (reshoots and rewrites will do that), it found its footing before the end of the series and I’m glad.

- Severance. If you’ve seen it, you get it; if you haven’t, you should.

- Slow Horses. I don’t know what took me so long to watch this show but once I started, it’s all I watched when exercising. I covered the first four seasons during the summer and finished just in time for the fifth season to start in the fall.

- Welcome to Derry. I liked the novel, IT, and the Muschietti’s Chapter One but I wasn’t as much a fan of Chapter Two. So I was tepid about this series. It ultimately delivered but the scope starts wide and takes it a while to find its footing and a solid pace. If you’re a fan of the book but not up for the show, the final two episodes are worth a watch.

I’d be making a mistake not to mention Stranger Things. We’ve been fans since day one and though the show isn’t wrapped at the time of this writing, we’re still here for it.

Podcasts

The podcasts I’ve listened to this year versus years past doesn’t vary wildly but a few dropped off and some new ones found their way to my rotatation:

- Deep Questions with Cal Newport

- Conan O’Brien Needs a Friend

- Smartless

- On Film with Kevin McCarthy

And One More Thing

Over the last few years, my oldest daughter has been interested in playing the guitar. A little over a year ago, she fell into it hard and has been both playing and songwriting since.

She and I started an ‘album swap’ for lack of a better term (what would you call this in 2025, anyway?) where she recommends an album to me, I recommend one to her, and we listen for a couple of weeks. Then we ask each other questions and have a discussion about it.

We also record it and I archive it for future listening. It’s something I really enjoy – and is meaningful – right now. Fast forward a decade or two and I’m sure it’s going to be that much more so.

To 2026

As with anyone else, this year was also full of other milestones for the kids, our family, trips, and so on. But everything above are the personal highlights all of which are largely outside of work.

As I wrote last year:

These are the highlights for 2024. Like most, I have things that I’m planning to do in 2025 though I’ll wait until this time next year to share how everything went.

And I repeat that but for 2026 instead.

In retrospect, it’s been an incredibly full year in nearly every facet. Such is life the older we – and our kids – get. I’m consistently surprised how much we fit into a year and even more so in just how fast it passes.

Nonetheless, each year brings with it a combination of pursuing the same goals and interests as well as moving into new areas, as well. In that regard, there will always be something new to share.

With that, I hope your year was just as full and mostly good and the next is even better. Here’s to 2026.