Quality Code and Bloat are two topics that I see a lot of developers either discussing and/or mentioning on the landing pages of their project pages.

I think the conversation around quality code is something that should always be happening. We should always be aiming to get better at what we’re doing, there is always someone who can help us, and there is always someone we can help.

It’s not that I think bloat is something we should accept, nor is it something that I think we should settle for in our projects (or those to which we contribute for that matter). But does it have as an objective definition as quality code?

It’s important to define clearly quality code and bloat as it relates to you, your team, and the solutions you’re providing for others. And I think this is true if you’re working for yourself, in a shop, for an agency, or even as a hobby and you’re building solutions for other people.

How I Define “Quality Code and Bloat”

Though I think the first part of this post was probably enough, it leaves a lack of clarity around how I tend to view both quality code and bloat in the projects that I work on for others and those I work on for myself.

So, naturally, I thought I’d share a little bit more.

Quality Code

When I’m working on projects for others, they generally consist of what you’d expect out of a WordPress project:

And, as I’ve discussed many times before, WordPress provides coding standards for PHP, JavaScript, and HTML. It’s possible to even evaluate your code against these rules before shipping it.

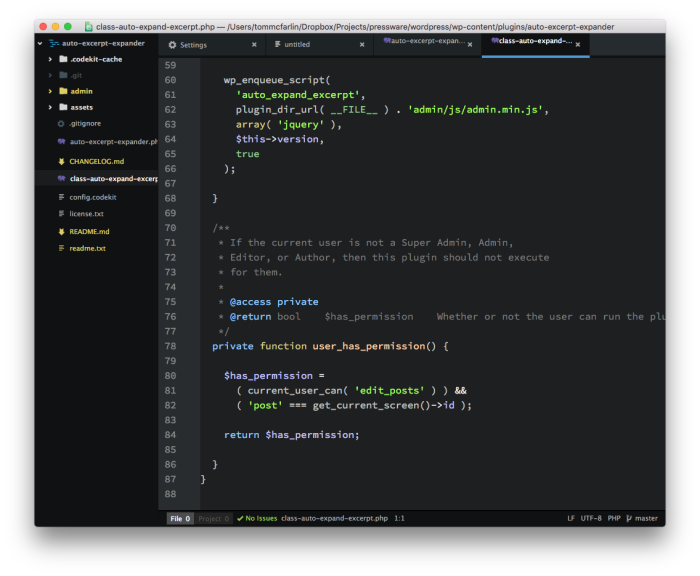

No issues from the CodeSniffer. :)

So when I’m working on a project, I actively work to make sure the code I’m writing adheres to these standards. This also includes code comments and so on.

This ensures that the code is not only up to what is expected of a WordPress project but that anyone who comes along to read the code or work on the code later knows what’s happening with it.

Bloat

When it comes to creating “production-ready” files, I use minification and lint tools to help with both JavaScript and CSS to make sure that the code that’s actually served to the browser is as small as possible.

Using CodeKit to manage bloat in a WordPress plugin.

I find that bloat is a little harder to define. As far as WordPress is concerned, I’ve seen it discussed in a number of ways (all of which may be correct, some of which may be correct, or some of which may not be correct at all:

- Files that aren’t used,

- Too many functions,

- Focus on backward compatibility,

- Not enough focus on backward compatibility,

- Lack of documentation,

- Too many comments,

- …and so on.

For whatever it’s worth, I do think that there are some definitions that make sense (and others that don’t), but that’s beside the point that I’m trying to make. For me, it’s a bit relative.

By that, I mean if you’re including both your un-minified JavaScript files and your minified JavaScript files, one may argue that it’s bloat. Then again, we’re talking about a few kilobytes some of which aren’t even sent across the wire.

I know you can script all of that to be removed during the build and deployment or packaging process, but one aspect of open source is that it helps others learn from the code you write (assuming that the code has a level of quality, right? :).

So when it’s a few kilobytes, the file is never served, and it has the potential to help someone else learn, I figure why not?

There’s More To This

It’s possible to take this further with tools like Scrutinizer and Travis CI for continuous integration. They are things that I don’t mean to gloss over, either.

The point isn’t about having the ultimate set of tools, though.

It’s about defining quality code and bloat in the projects you’re working on and making decisions as to what you will and won’t accept when it comes to the code that you release for others to use.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.