One of the things that I find consistently interesting (both from a programming standpoint and from a WordPress standpoint), is this:

I like keeping code separated such that code responsible for interacting with WordPress is relegated to its namespace while the rest of our code is namespaced appropriately elsewhere.

I think this is obvious, though.

When it comes to writing code, though, this doesn’t mean it has to be left simply to the how we write our classes and then organize them. What about things at a slightly more granular level?

That is, what if we were to look at methods as part of the larger whole and make sure they’re doing their job well, too? Sure, people like Bob Martin have been writing about this kind of stuff for the majority of their career and preaching it to people like us.

But these concepts are something that you simply start doing and then apply them for good. Paradigms shift, we’re better today than we were yesterday, and there may be multiple ways to achieve the same kind of thing.

So when it comes it comes to creating readable WordPress functions for a specific domain, what might that look like?

Readable WordPress Functions

For those who are familiar with the SOLID principles or anything that talks about writing good code, one of the things that many of those people write about are the length at which a method should be.

I tend to take them as rules rather than law because sometimes, methods just can’t be that short. I mean, I guess they could, but at some point it feels like micromanagement of code, right?

And doing something for the sake of doing is one thing, but doing something for the sake of meaningful programming is another. I’ll choose the later each time.

Anyway, so here’s an example: Let’s say that you have some code that’s called via Ajax and before proceeding with the operation, you need to know if a custom post type exists.

The steps for doing something like this might go as follows:

- initiate the Ajax call,

- check the security nonce to verify it’s a valid request,

- check to see if data exists,

- if it does, then return a success message; if not, return an error message.

All of this can be done within a single message, sure, but let’s assume that we want to write this in a series of calls that are easy to read where the code is self-documenting, to a degree (this doesn’t mean I’m against comments – I’m not at all, but that doesn’t mean we want our code to be unclear, does it?).

First, the Ajax call:

Then we have a function on the server side for explicitly verifying the security nonce (this, of course, assumes you’re correctly setting it up on the front-end):

After that, we want to check if data exists:

From here, we’re then able to work with the Ajax response object by evaluating its success property and reacting accordingly.

Going a Step Further

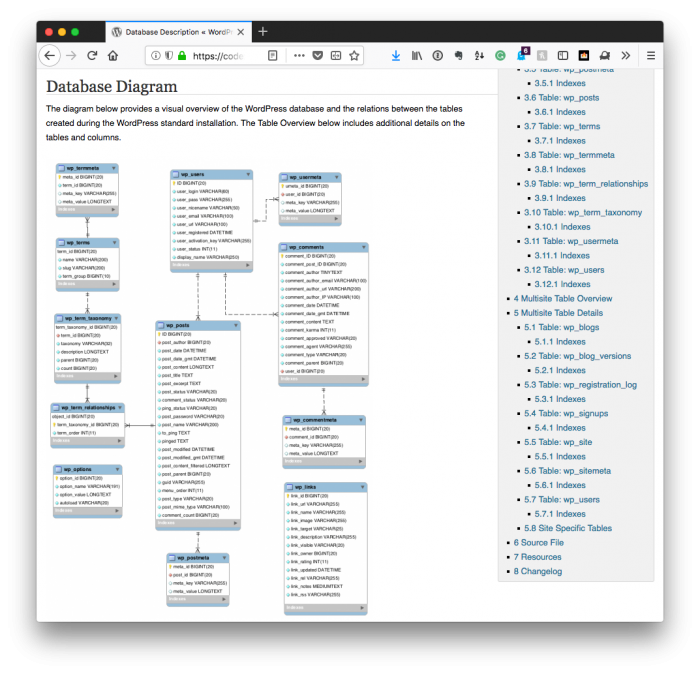

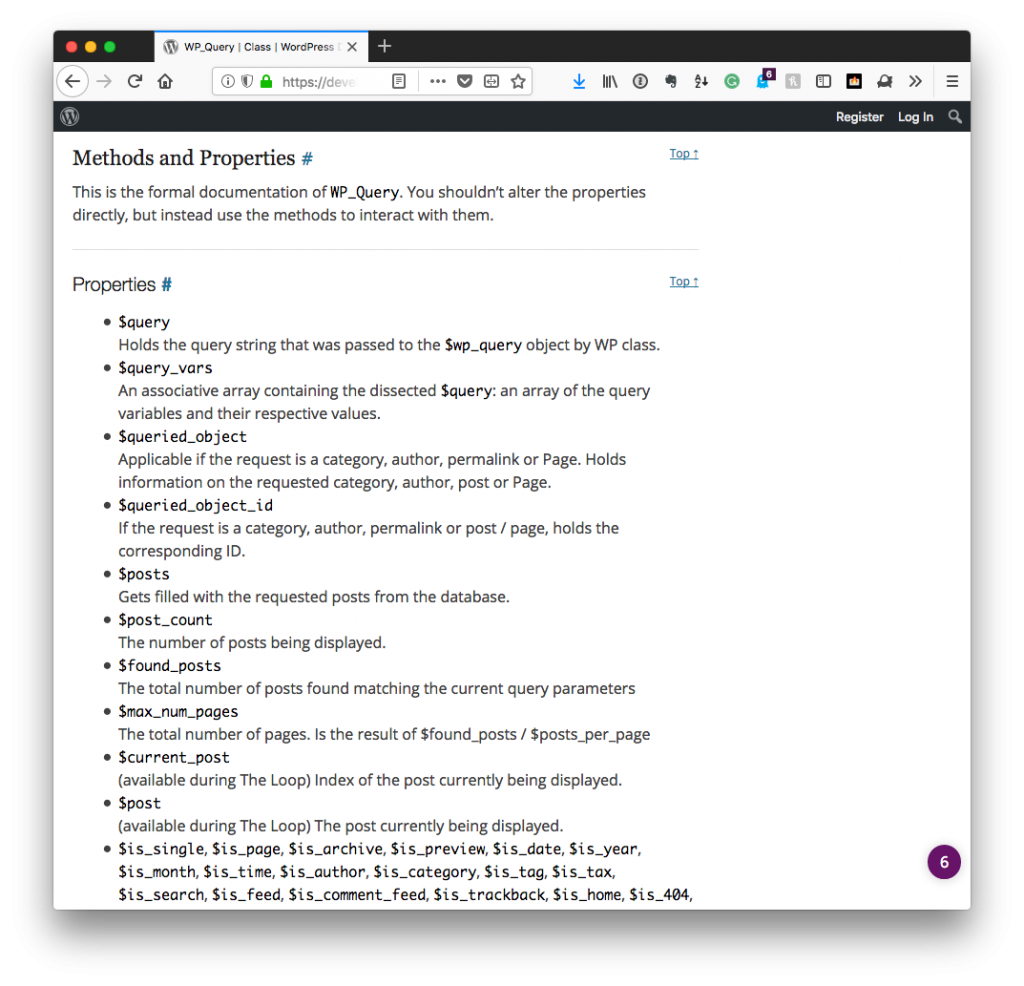

Let’s take this a step further though and say that products do exist and we want to retrieve all of their post IDs. Doing this with WP_Query is pretty easy but let’s say, for kicks, we want to interface with the database directly.

Note this is more of an exercise of showing a way of doing something rather than arguing for using $wpdb over WP_Query. That’s content for a whole other post.

Anyway, so we’ve determined that data does exist. So let’s grab an array of all of the post IDs and return it or an empty array. Perhaps this would look something like this:

Once the values are returned, we can then operate on them however we see fit.

What’s the Purpose of All of This?

Generally speaking, it’s to help us think about code in such a way that we’re able to read it almost as close to the written word as possible. That is, we’re able to point to a piece of code as say:

First, we’ll see if something exists. If not, we’ll send an error; otherwise, we’ll grab the data and then work on it.

Granted, I’m talking in less concrete terms here, but that’s because I don’t necessarily know what you’re working with any more than you know about my work. But you get the idea, right?

And furthermore, if you’re looking to unit test code that’s de-coupled from WordPress, this can be done through the use of interfaces that mock the functions or even that run direct queries against the database without needing to use WordPress.

But, as with some of the points mentioned above, that’s topic for a different post.