When it comes to creating classes for WordPress plugins, I’ve been asked about why I bother separating functionality into subscribers and into other classes.

I think this is a good question because it helps to understand two things:

- the role of a subscriber as it relates to the WordPress architecture,

- the role of the other classes as it relates to what it is you’re building (and how this can help with other things like unit testing and so on).

So I thought why not respond in the form of a short post? It’ll document the why behind the what .

WordPress Programming: Subscribers and Domain Objects

I consider the classes that are not subscribers domain objects that come from the software development approach of domain-driven design.

That’s outside the scope of this post but worth mentioning if for no other reason that it gives some context to what would otherwise be considered jargon.

1. Subscribers

But first, subscribers.

Since WordPress is based around a hook system – a system that’s predicated on the event-driven design pattern – it’s helpful to have a class that responds to whenever an event is raised.

This can be for any pre-defined WordPress hook or any custom hooks. It does not matter.

And I don’t want to make the class more complicated than necessary so I tend to think of them like this:

A subscriber responds whenever a specific event happens.

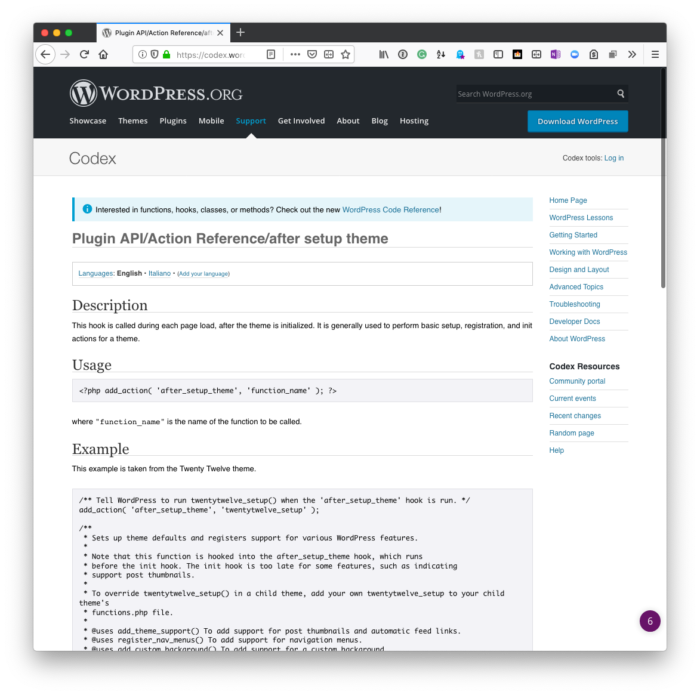

And that’s it. This event can be something like after_theme_setup or the_content or even init. It doesn’t matter.

It waits for an event to happen then responds in whatever what we decide through the use of other code (which is where domain objects come into play).

2. Domain Objects

These may also be called business objects or something similar. The idea behind them is this:

Everything that we do in object-oriented programming is meant to solve a particular problem and it’s meant to do so through some type of object that represents a real-world object or at least a concrete idea.

So whenever you’re working to provide a solution for someone, the classes that you’re writing – the objects they will become when instantiated – are the domain objects.

These are also the classes that do the actual work. So you can think of it in three components:

- WordPress. The core application, of course, that raises the event to which the subscribers respond.

- Subscribers. The set of classes responsible for listening for a specific event and then instantiating the proper object to handle the code.

- Domain Objects. The code that actually does the work of taking a set of data, operating on it, and then potentially returning a value.

The domain objects are where the code for actually doing something lives. The subscribers are like the connection between WordPress and said functionality.

Subscribers say “This event has happened and and this class is capable and responsible for handling the results of it.”

What About Testing and So On?

Earlier in the post, I talked about how domain objects are related to unit testing and other quality control-related programming techniques.

Though this isn’t the post for the details, it’s worth mentioning that keeping domain objects and subscribers de-coupled from one another (and, in turn, from WordPress) allows us to instantiate, test, and work with objects that are invoked by subscribers without needing to bring along WordPress into our work.

And this is something that can be immensely helpful when building larger solutions. But the gist of how to do that is content for another post.