However you’ve come across this article, it’s the eighth in which I am evaluating the claims of another developer’s article – What Do You Expect From Being a Software Developer?

From the first part in the series:

At the very least, perhaps these things will be something to keep in mind if you’re looking to enter the industry or even for who have been working in the industry. At most, that article is something that provides a solid perspective from one person’s experience (which likely echo many others, too).

And I’ve been slowly working through each point since. In this post, I’m looking at one that states: Uncertainty will be your toxic friend.

The Relationship of Software Development

Originally, I planned only to go through the list of things provided in the post and comment on them, but the idea of relating “uncertainty” and “toxic friend” piqued my curiosity a bit.

On Toxic Friendships

To that end, I decided to dive into the various corners of the Internet to see how “toxic friend” is defined.

- [A toxic friend] is usually someone who brings elements of dysfunction and unhealthiness into the relationship dynamic or group. Psychology Today.

- Toxic friendships can take different forms, but they generally drain you mentally and have a way of bringing you down instead of building you up. Healthline.

- Signs of a Toxic Friendship as outlined by Psych Central.

- [Toxic friends] often backstab, gossip, lie, act selfish, use, belittle and even manipulate and are taking more than giving back to the friendship. Urban Dictionary.

- A toxic friend is someone who consistently exhibits harmful behavior, such as manipulation, negativity, or betrayal, causing emotional distress and negatively impacting the well-being of the relationship. ChatGPT (and all of the sources who trained the underlying model).

This isn’t meant to be completely facetious as there is validity in what’s said, but I generally consider “uncertainty as part of the job” and nothing more. But personifying it as a toxic friend? Maybe that makes sense. Maybe not.

Uncertainty in Software Development

Here’s my experience, point by point.

Third-Party APIs

[Implementing] something in your project you never worked with, eg. 3rd party API – how are you going to implement something you aren’t familiar with?

This is true.

Whenever we’re tasked with having whatever application we’re working on interface with a third-party, there’s almost always a learning curve. (I can’t think of a time where there wasn’t but I can’t speak for everyone so I don’t want to speak in absolutes.)

Sometimes, the learning curve is steeper. It depends on, say,

- authentication to access the API,

- the arguments for the API,

- and how to process what it returns.

Further, if the documentation for the API is wrong then it’s a matter of looking at what’s returned and trying to figure out how best to work with it, or it’s a matter of hoping whoever supports the API is willing to look it, offer guidance, or perhaps even update the endpoints.

Regardless, learning how to integrate with a new API is one thing. Hoping the documentation provides exactly what’s needed or finding a resolution if it doesn’t is another level of complexity for which we ought to plan.

Learning a New Technology

[Transfer] to a new project, with new technologies – you will think about how you are going to be efficient and productive with something you need to learn?

I’d go as far to say that this is something that may still be challenging even working within the same segment of the industry.

For example, if you’re working with one organization and they have certain:

- coding conventions,

- branching and merging strategies,

- continuous deployment set ups,

- testing methodologies,

- and so on,

And then you move to another organization that differ, even if it’s just in one area, then it’s something new to learn.

Lay all of that on top of moving from one stack to a completely new stack and you’ve got a handful of new tools, technology, and methodologies with which you need to work.

Again, this isn’t just one level of uncertainty. It’s multifaceted.

Moving To a New Company

[Move] to a new company – you are unsure how you are going to settle in and vibe with new people.

I don’t think this is something that’s deserving of much more commentary than I’ve already offered especially in the previous section.

It’s worth noting, though, that in our field it’s far more likely you’ll be changing jobs than not. This isn’t to say that you can’t – or won’t – stay at a place for a very long time, but the statistic for programmers changing jobs used to be something like every three-to-five years or so (CodeMotion). I’ve also read statistics that it can be as frequently as every two years (Invene).

I’m not arguing for or against this. (Personally, I think each person needs to do what’s best for himself or herself.) But it’s worth noting this will obviously require having to learn new things especially if you’re expecting to move to a new company.

Bug Reports and Deadlines

[Bug] report on the day you need to finish the work – you fear that you are gonna break the deadline

If I was to give a TL;DR to this section, it would be something like this: Yes, I agree. But I also contend that, if given you opportunity, as how project management works at the organization in question. Because they can make or break this particular level of uncertainty.

I have a longer take on this, too.

Yes, this happens from time-to-time but there are safeguards that can – or maybe should? – be placed around any given sprint of work to account for this. And if you have a good project manager, then it shouldn’t be a problem.

For example, let’s say you have a sprint and you and your team have completed all of the necessary work to ship the sprint to QA or whoever will receive the work. But just before you’re tagging the release, a bug report comes in from the prior sprint that affects the work in this sprint.

As frustrating as it can be, it’s also something that should be expected. It’s one of those “hope for the best, plan for the worst” situations.

That is, each time a new sprint has started, there can (read: should) be time built into the new sprint such that it accounts time for bug reports to be introduced so they can be addressed.

No, you can’t anticipate how many nor reports you’ll receive nor can you anticipate how said bugs will be to resolve so there’s always a level of uncertainty in the planning, but if you’re adding time to your sprint to account for this then there should be less stress in missing the deadline because you’ve accounted for the uncertainty.

Then, you’ve got a best case/worst case scenario: Either you’re going to ship everything you planned earlier than expected or you’re going to ship what you’ve planned in addition to fixes.

On certain teams, perhaps you’ll even be able to grab another task from the next sprint and bring it into this sprint. That’s a positive outlook on uncertainty.

On Job Security

[Job Security] – economic situations, pandemics, wars, and other factors heavily affect this industry which results in layoffs

There’s really not much to contribute to this. Few parts of the economy are immune to factors that may negatively impact employment.

I don’t find this unique to working in tech. This, above all other criteria, is something for which we should always plan.

The only commentary I have on this is that if you have the ability to save for three-to-six months of your expenses, then that can sometimes help offset when these things happen.

New Technology (Tools and AI)

[The] evolution of technology – you are never sure if tomorrow you are gonna be replaced by some new technologies like AI

This point is the one I’ve had to consider the most because, for the 15+ years I’ve been working in this field, I’ve never truly been worried about a new piece of technology – be it software or hardware – replacing anything I or any of my colleagues jobs.

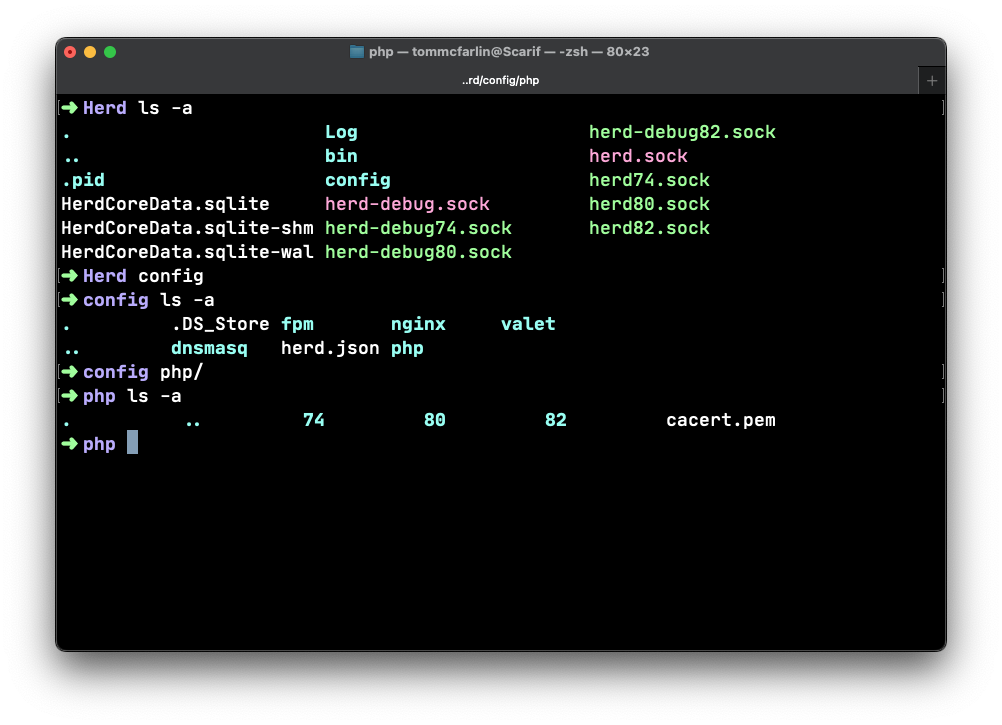

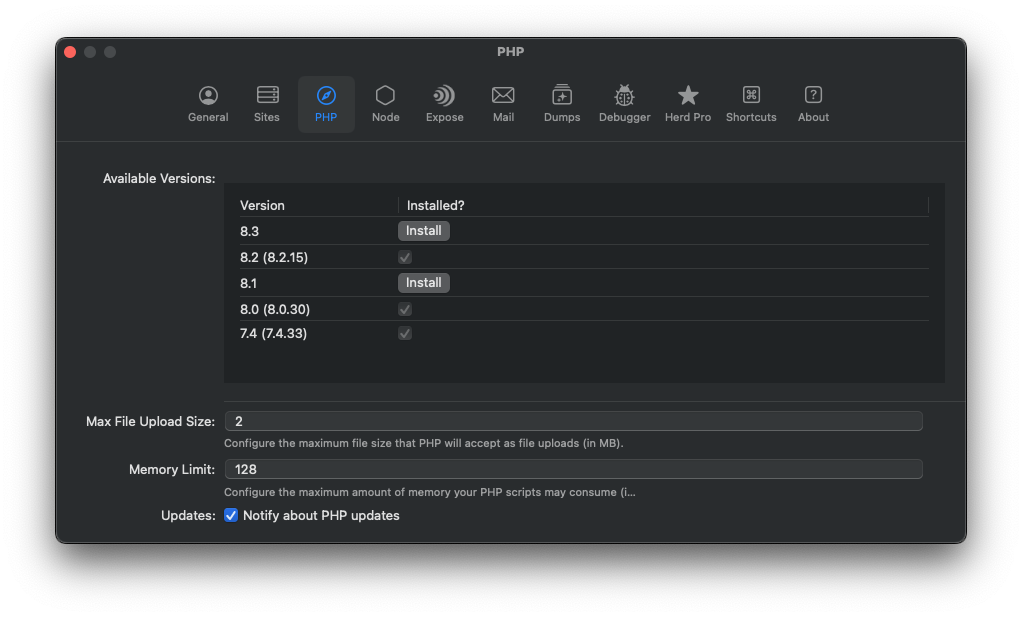

NEW TOOLS

If anything, as new tools have come – and some have gone – they were things that we were expected to learn and sometimes incorporate into our day-to-day work. They weren’t advanced enough to replace anything we were doing. They accelerated what we were doing, sure, but only after successfully learning said tool.

And even though we’re in a surge of tools being built with AI, it’s still not something about which I’m worried taking my job. If anything, it’s helping me get more work done quicker and it’s helping us to build tools that enhance our software if anything else.

AI

That said, I can only really speak as to how AI is affecting or impacting my job as a software engineer. I can’t speak to how it may affect someone in this industry that’s engineering-adjacent but I still don’t yet see how it’s going to truly replace a given job.

Even the tools that promise to help plan schedules based on, say, the backlog of tasks and the availability in each person’s calendar, it also makes the assumption that the data it’s being handed is up tot date and we’re assuming it can correctly estimate based on the data it’s given.

AI’s impressive, to be sure, but there’s a lot of assumptions happening based on the solutions it provides and those assumptions can cost a lot of money without the proper safeguards in place.

If anything, AI is enhancing the way we get things done and it’s allowing us to build tools that we couldn’t do so two years ago. But there still has to be someone able to interface the software being built with the AI to which its communicating. And there has to be someone to make sure the models are returning data that’s relevant to what’s being asked.

There’s still much to be explored within the field of AI and it’s something I think all technologists should be following. This isn’t because we should be looking over our shoulder for what’s coming for us, but look at how we can use this to help us in our day-to-day.

Certainly Uncertain

Though I largely agree with all of this, the biggest difference I have is treating uncertainty in and of itself as anything different than something that comes with this job. I don’t think the original article was disputing this fact. If anything, it explains what to expect so you’re not surprised.

But if I’m sticking with the analogy, is uncertainty something that “brings elements of dysfunction and unhealthiness into the relationship?” I don’t know if I’d go that far. Learning something new, how to interface with a third-party service, or working with some other technology isn’t necessarily dysfunctional nor is it unhealthy.

It can be exhausting, it can be challenging, it can be frustrating, it can be exciting, but it can be expected.

So as much as I agree with the article and as much as I think uncertainty is something we all should expect, I generically don’t consider it toxic.